By Daniel Heimsoth, Physics PhD student

Simulating quantum systems on classical computers is currently a near-impossible task, as memory and computation time requirements scale exponentially with the size of the system. Quantum computers promise to solve this scalability issue, but there is just one problem: they can’t reliably do that right now because of exorbitant amounts of noise.

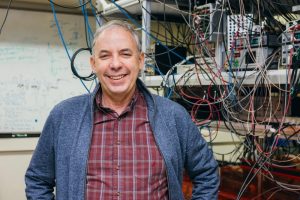

So when UW–Madison physics postdoc Pooja Siwach, former undergrad Katie Harrison BS ‘23, and professor Baha Balantekin wanted to simulate neutrino evolution inside a supernova, they needed to get creative.

Their focus was on a phenomenon called collective neutrino oscillations, which describes a peculiar type of interaction between neutrinos. Neutrinos are unique among elementary particles in that they change type, or flavor, as they propagate through space. These oscillations between flavors are dictated by the density of neutrinos and other matter in the medium, both of which change from the core to the outer layers of a supernova. Physicists are interested in how the flavor composition of neutrinos evolve in time; this is calculated using a time evolution simulation, one of the most popular calculations currently done on quantum computers.

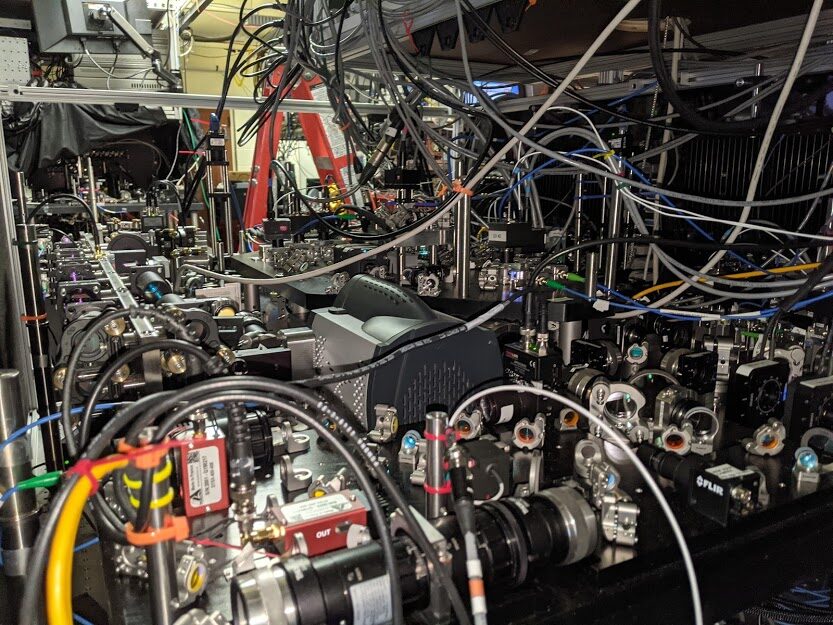

Ideally, researchers could calculate each interaction between every possible pair of neutrinos in the system. However, supernovae produce around 10^58 neutrinos, a literally astronomical number. “It’s really complex, it’s very hard to solve on classical computers,” Siwach says. “That’s why we are interested in quantum computing because quantum computers are a natural way to map such problems.”

This naturalness is due to the “two-level” similarities between quantum computers and neutrino flavors. Qubits are composed of two-level states, and neutrino flavor states are approximated as two levels in most physical systems including supernovae.

In a paper published in Physical Review D in October, Siwach, Harrison, and Balantekin studied the collective oscillation problem using a quantum-assisted simulator, or QAS, which combines the benefits of the natural mapping of the system onto qubits and classical computers’ strength in solving matrix equations.

In QAS, the interactions between particles are broken down into a linear combination of products of Pauli matrices, which are the building blocks for quantum computing operations, while the state itself is split into a sum of simpler states. The quantum portion of the problem then boils down to computing products of basis states with each Pauli term in the interaction. These products are then inputted into the oscillation equations.

“Then we get the linear-algebraic equations to solve, and solving such equations on a quantum computer requires a lot of resources,” explains Siwach. “That part we do on classical computers.”

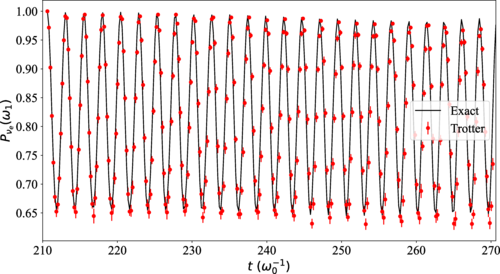

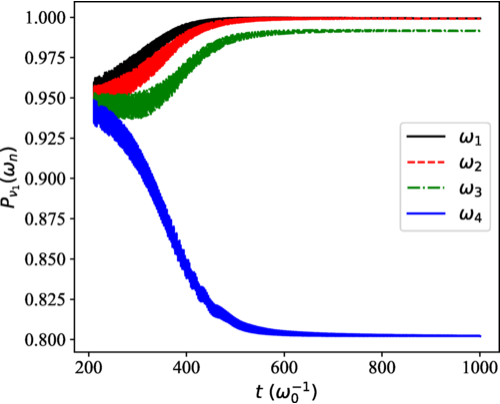

This approach allows researchers to use the quantum computers only once before the actual time evolution simulation is done on a classical computer, avoiding common pitfalls in quantum calculations such as error accumulation over the length of the simulation due to noisy gates. The authors showed that the QAS results for a four-neutrino system match with a pure classical calculation, showcasing the power of this approach, especially compared to a purely quantum simulation which quickly deviates from the exact solution due to accumulated errors from gates controlling two qubits at the same time.

Still, as with any current application of quantum computers, there are limitations. “There’s only so much information that we can compute in a reasonable amount of time [on quantum computers],” says Siwach. She also laments the scalability of both the QAS and full quantum simulation. “One more hurdle is scaling to a larger number of neutrinos. If we scale to five or six neutrinos, it will require more qubits and more time, because we have to reduce the time step as well.”

Harrison, who was an undergraduate physics student at UW–Madison during this project, was supported by a fellowship from the Open Quantum Initiative, a new program to expand undergrad research experiences in quantum computing and quantum information science. She enjoyed her time in the program and thinks that it benefits students looking to get involved in research in the field: “I think it’s really good for students to see what it really means to do research and to see if it’s something that you’re capable of doing or something that you’re interested in.”